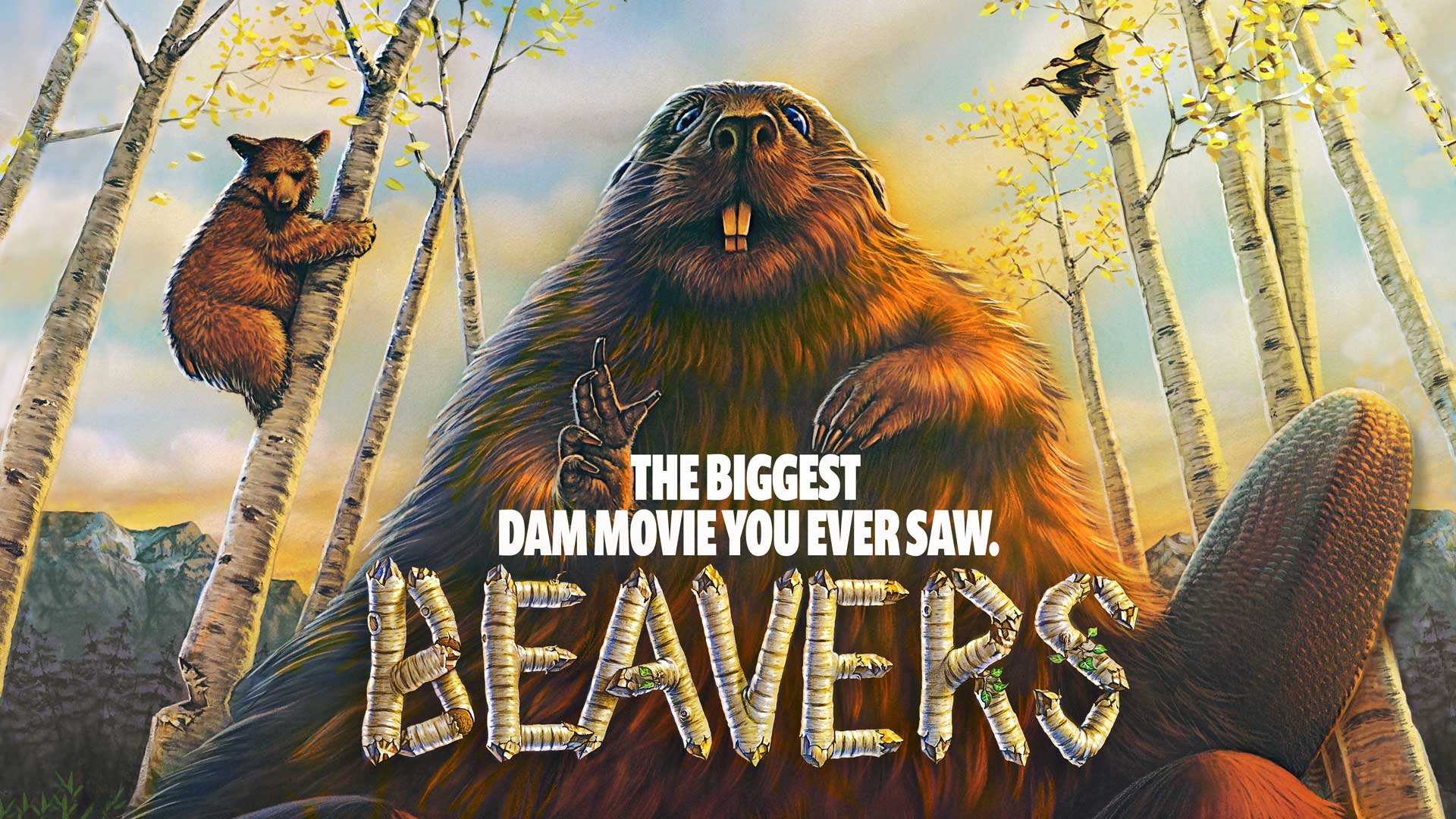

Beavers

The Director’s Cut

Welcome back the furry critter that changed the landscape. Three decades after its original release, Beavers, the worldwide family favorite, returns to giant screen theaters better than ever. Filmed with IMAX® cameras entirely in 15perf/70mm motion picture negative and digitally remastered at 8k for IMAX with Laser and other digital systems, the new Beavers “Director’s Cut” features spectacular new aerial wilderness scenes and a soundtrack remastered with 12.1 surround-sound for maximum impact.

First released in 1988, Beavers was the first giant screen feature with a natural history focus on a single creature. Exhibited in IMAX® and other giant screen theaters, the film’s furry stars and their story garnered awards and drew extensive family and school audiences and more than 10 million viewers across the planet. Beavers has screened in 21 countries in 17 different languages and remains distinctively, “the Biggest Dam Movie…Anyone Ever Saw” and for the choosy, the ultimate giant screen treat. The film is now set to wow new generations of audiences.

Synopsis

Set against the stunning and rugged backdrop of the Canadian Rocky Mountains, Beavers tells the story of a family of beavers as they grow, play and transform the world around them. The film begins with two beavers off to find a place to build a new home. Fighting adversity and exhibiting enormous perserverence, the pair build a lodge, raise a family and transform their habitat on an astounding scale.

With the giant screen relaunch of Beavers, new generations of movie-goers will have an opportunity to adventure in the Rockies, swim with this shy, hard-working creature, and discover its remarkable contribution to the natural world.

In Theaters—(where to see Beavers)

For theater locations: Where-to-see Beavers

Trailer

Theme & Inspiration

The beaver, nature’s greatest engineer and a patient builder of wetlands, remains a key player in North American ecosystems—more vital than ever in an era of shifting climate conditions. The wetland environments shaped by the beaver help reduce major flood events and maintain biodiversity. Although its natural habitat continues to be eroded worldwide, in recent decades, beavers have been reintroduced to a number of regions across the Eurasian continent in efforts to help restore and maintain wetland habitat. With the giant screen relaunch of Beavers, new generations of movie-goers will have an opportunity to adventure in the Rockies, swim with this shy, hard-working creature, and discover its remarkable contribution to the natural world.

When it was first released, the film’s intimate portrayal of the beaver and its aquatic world helped usher in a new era of giant screen natural history filmmaking and encouraged the introduction of IMAX theaters in natural history museums. In 2004, Beavers became the fifth film ever to be inducted into the Maximum Image Hall of Fame.

The Production

Production Notes

How was the film Beavers made? The article below describes some of the unique challenges that were overcome to put beavers on the giant screen.

In 1986, filmmaker Stephen Low was asked to develop a film concept for the Nagoya Regional Office of the Dentsu Corporation in Japan and their client, the Chubu Electric Power Company. Low suggested a wildlife theme: a true story about one of nature’s greatest engineers, the beaver. The previous year (1985), Stephen Low’s first giant screen film Skyward had debuted at the Tsukuba Expo in Japan. With Skyward, director Stephen Low and a team which included producer Roman Kroitor, wildlife expert William Carrick and director of photography Leonidas Zourdimas, had recorded intimately and unforgettably the elegance of Canada Geese in flight.

With Beavers, the challenge was to produce an equally intimate film about a very different kind of animal. “Our aim” says filmmaker Low, “was to use the amazing resolution and size of the 15/70 format to totally immerse the viewer in the world of the beaver. We wanted to allow the audience to swim and play amongst these creatures, face dangers with them and know their story.”

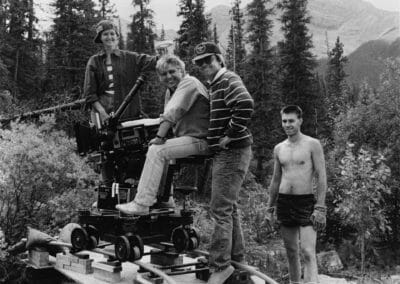

To tackle the project, a production team was assembled which included: production manager, Pietro Serapiglia; wildlife consultant, William Carrick; and director of photography, Andrew Kitzanuk. The IMAX® camera began rolling in February 1987 near Port Perry, Ontario in frigid waters under nearly 2 feet of ice. Behind the camera for the under-ice sequences, was underwater cinematographer, Mal Wolfe.

Getting the beavers’ story was not an easy operation. The beavers filmed for the production were hand-reared in a natural setting under the care of wildlife expert, William Carrick. Accustomed to the presence of humans, but untrained, the beavers went about their business while a patient camera crew watched and waited for just the right moments. No one involved in the project was completely convinced that enough of the beavers’ behavioral traits would be recorded on film before time and money ran out. The beavers after all, were proceeding at their own pace.

“I think wildlife is probably one of the best uses of IMAX,” says director Low, “because wildlife see things differently than we do and IMAX, more than any other medium, enables us to see and feel and live like they do. The real magic of wildlife in IMAX is that it lets you be with living things in places you’ve never been before; it’s not to see what it’s like to be on a roller coaster which we’ve all been on before anyway.” Low goes on: “The real roller coaster is when you’re flying in formation with a goose or swimming underwater with a beaver and living inside a beaver’s house. It’s cutting down a huge tree and being at the beaver’s perspective when it falls. We simply can’t experience wildlife with that intimacy and reality on television. Wildlife on television is so removed and distant… and more than ever, I think people need an opportunity to see and experience the world of living things around us.”

Much work went into searching for ideal locations for the dam-building and underwater sequences. Director Stephen Low, and production manager Peter Serapiglia, flew and drove over thousands of miles of Alberta territory to find suitable dam sites. In addition, Low spent several weeks in a wetsuit, climbing in and out of rivers, lakes and ponds all over Alberta looking for crystal clear water in which to photograph the beavers’ activities.

The stunning scenery and clear waters of Kananaskis Country, Alberta in the heart of the Canadian Rocky Mountains provided the principal location for the film. Filming above and below water at several different locations and at three different dam sites throughout the area, director Low and crew were able to put together an accurate and detailed portrayal of the dam construction process: from tree cutting to the finished product. The final dam depicted in the film was found in Kananaskis Country and was some 300 feet long.

To capture the mammoth proportions of the final dam and the sweeping extent of the beavers’ transformation of the land, director Low, director of photography, Kitzanuk and the IMAX camera, were suspended in a basket under a 150 foot construction crane and swung in a gigantic arc over the landscape.

In contrast to the all-encompassing view provided by the crane, the team developed a special device to record the life of the forest from the beavers’ point of view. Nick-named the “beaver-cam,” the device was a simple bracket which allowed the heavy IMAX camera to be hand-held barely half a foot above the ground. This made it possible for the camera to follow the unrehearsed and unpredictable activities of the beavers and other animals of the forest.

Speaking of the team’s labor over many months, director Stephen Low said: “we succeeded, in fact, in getting far more than I had anticipated in the way of beaver activity. In some ways we were very lucky: the beavers performed very naturally and were uninhibited by our presence, we lost only one week of shooting to bad weather and our production team was as dedicated to the project as any director could have asked.”

About the Film

- Production Format: 15/70

- Duration: 34 min.

- Re-released: 2019 as Beavers–The Director’s Cut

- Original release date: 1988.

- Produced by: Stephen Low Productions Inc.

- Distributed by: The Stephen Low Company

- Available for license: IMAX Digital, 15/70.

- For licensing information, contact: The Stephen Low Company

Credits

- Stephen Low, Director/Producer/Underwater Cinematographer

- Takashi Yodono, Executive Producer

- Peter L. Serapiglia, Production Manager (Beavers) Producer, The Stephen Low Company

- Andrew Kitzanuk, C.S.C., Director of Photography

- Eldon Rathburn, Music

Media

Clippings

“2 thumbs up”.

—Siskel & Ebert

“Leave it to ‘Beavers’ – IMAX’s Latest Triumph”

—L.A. TIMES

“Breathtaking”

The New York Times

“Beavers: a fine documentary that shines on the IMAX screen”

—Seattle Times

Beaver Facts

Some background on the beaver.

Educators: to download the teacher’s guide for Beavers, please visit our educators page.

The beaver is an amphibious rodent (order Rodentia) of the family Castoridae and the genus Castor. There are two species of beaver: the North American Castor canadensis, and the similar European Castor fiber. The beavers’ prehistoric ancestors include Castor californiensis and Castoroides ohioensis, a creature which weighed between 700 and 800 pounds. The film Beavers features the Castor canadensis which, while native to North America, can now be found in Europe and Asia as well.

The contemporary beaver has soft brown fur, a leathery paddle-shaped tail (crisscrossed by a scale-like pattern) and characteristic rodent teeth which are used principally for gnawing wood. The beaver is the largest of rodents, with the exception of the amphibious capybara of South America. A mature beaver measures about 48 inches in length and generally weighs between 40 and 60 pounds, although some may weigh much more than this — the record was set in 1921 by a beaver from Wisconsin, which was reported to weigh 110 pounds. Beavers have poor eyesight which is compensated for by acute hearing and an excellent sense of smell.

The leaves, twigs and bark of deciduous trees make up the beavers’ principal diet, with the aspen tree being a particular favorite when available. In order to effectively digest this diet, bark and wood are pre-digested in a special gland, excreted, re-eaten and then re-digested (in a manner similar to the digestive process of a rabbit). Beavers do eat a variety of other vegetation, including floating duckweed, pond lily leaves and roots, bulrushes, bracken fern, tender green grasses, and even algae.

Excellent swimmers, beavers can swim submerged for half a mile or more. They can constrict muscles in the ears and nose to prevent water from entering and they can also close their lips behind their incisors to keep water out of the mouth while cutting submerged branches. If not overly active, these creatures can stay under water for at least 15 minutes. When swimming in winter, beavers will make use of air bubbles and air pockets trapped under the ice to extend the time they can stay submerged. In an emergency situation, oxygen-rich blood otherwise being used by muscular areas of the beaver’s body can be redirected to the brain.

Beavers live in colonies. A colony may contain as little as two or as many as a dozen beavers and is located in a stream, lake or pond. Often a colony of beavers will create their own pond by building one or more dams across a stream or other water source.

Within a colony the beaver is a highly social creature. Beavers exhibit intolerance to alien beavers however, and have been known to attack and even kill an intruding one. To mark the boundaries of the colony’s territory, beavers secrete a yellow-orange liquid called castoreum from the castor glands, a pair of glands located under the skin at the base of the tail.

Beavers are nocturnal animals; while they are seen during the day, much of the beavers’ work is accomplished during the evening and night hours. One beaver or two beavers working alternately, can gnaw through the trunk of a tree fairly quickly. A tree three to four inches in diameter can be felled in under an hour. During the course of a year, two beavers may fell as many as 400 trees, some of them over a foot and a half in diameter.

Usually trees are cut within about 150 feet of the shoreline. When a tree has been felled, several beavers may participate in removing branches, cutting up limbs and dragging or floating the material to a chosen site. At the site, branches and limbs are progressively interwoven to produce a solid structure which is then sealed with rocks, mud and grass.

A dam may grow to well over 100 feet in length and the pond behind it may grow to cover several acres, providing the beaver colony with a good refuge from land-based predators. Some dams have been reported to reach well over a thousand feet in length, creating a lake with numerous lodges. In the giant screen film Beavers, the large dam is some 300 feet in length. In preparation for winter, the beavers will work to ensure that the dam is sufficiently high and the pond deep enough to prevent the water from freezing to the bottom.

For living quarters, the beavers will construct a dome-shaped house or lodge, also made of wood, mud and grass. The lodge is located in the middle of the pond, or attached to the bank of a lake or stream. Typically a lodge is about six to ten feet in diameter. Located inside the lodge and above the water level is a living chamber accessible only through underwater tunnels, of which there may be several. With the exception of a vent hole at the top of the lodge, the walls are coated with mud to provide good insulation. Over a period of years a lodge can become very large (over 20 feet in diameter and 12 feet in height) and develop several living chambers. The walls may be built up until they are over two feet thick. Beavers may also burrow into soft earth on the banks of streams or ponds, creating one or more chambers for rest and feeding.

A beaver colony contains only one active adult pair who will mate for life. Mating takes place in water in early February and beaver kits are born in early May (a gestation period of 100 to 110 days). A female will typically produce her first litter around her third birthday. A litter will usually consist of three to seven kits, although litters of up to 12 have been recorded. As with many creatures, the size of the litter varies with the age of the female, the availability of food, and the density of the population.

Kits will nurse for two to two and a half months. By the fall, the beaver kits are assisting in the winter preparations of the colony: gathering and storing food, and building dams and houses. By the time winter sets in and the pond freezes over, the kits will weigh anywhere from 11 to 28 pounds, depending upon the food available in their habitat.

Most of the young beavers will leave the colony in early spring in search of a good place to start a new family. These migrating beaver are particularly susceptible to attacks from predators such as wolves, coyotes, lynxes, bobcats, mountain lions, wolverines, bears and otters, or even from other beavers whose territory they have transgressed. Generally only a few beaver from a litter will live to reach five years of age (the survival rate may be as low as 12% ). Beavers may live to be much older however, and some have been found to have lived as long as 20 years.

The beaver has long been of economic and religious importance for the native peoples of North America. For thousands of years Indians have trapped the beaver for its meat and fur, and saved a space in their religious ceremony for the creature. With the coming of Europeans to the continent in the 16th and 17th Century, beaver fur became an important commodity in the trade between First Nations and colonists, and between North America and Europe. Indeed, the fur trade, of which beaver pelts were a major component, provided much of the impetus for early exploration and settlement of the continent. The trapping and selling of beaver pelts continues in the present age.

To many, the beaver is a destructive animal and a nuisance. This is particularly the case with farmers and others who have found their land being flooded as a result of these creatures hard work. Yet, within the realm of nature the beaver plays an important role, transforming the environment as no other creature on Earth save humans. Through dam-building, the beaver creates a water habitat for an infinite variety of new creatures. When the dam eventually breaks and the water drains from the pond, the land beneath will become rich and fertile meadow.