Super Speedway: the Making of a Motion Picture Classic

Racing Wow.

In 1997, Super Speedway became the first large-format film to capture on-track racing action at actual race speeds. The company developed camera mounts that enabled onboard filming from an Indy Car with an IMAX camera at speeds of up to 240mph. Filmed from an Indy Car supported by Newman-Haas Racing and driven by racing legend Mario Andretti, Super Speedway pulled audiences into the world of championship auto racing and accelerated them to a new giant screen high. Super Speedway became an instant classic of the giant screen and two decades later is still the definitive motion picture racing experience.

Mario Andretti drives the camera car for an on-track point of view shot at Homestead speedway in Florida. (Frame from Super Speedway).

How the Film was Made

The development of Super Speedway got under way in 1993. Stephen Low, a longtime enthusiast of open-wheel racing, had harboured the dream of producing a film about auto racing since his father, acclaimed filmmaker Colin Low, filmed Jimmy Clark winning the Indy 500 in 1965.

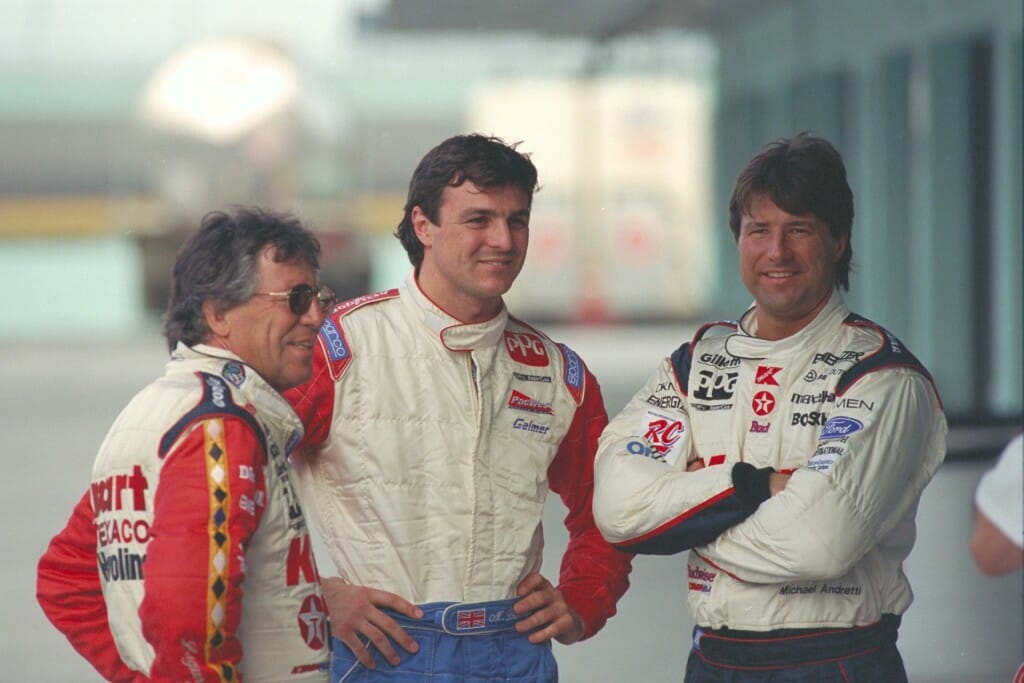

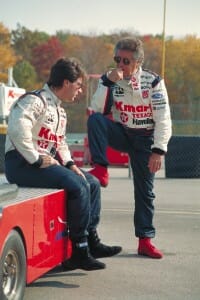

Michael Andretti (left) and Mario Andretti (right) confer during filming for Super Speedway. Photo: Patrick Gariup.

From start to finish, the Super Speedway project took just over four years. By the time the pieces of the production puzzle fell into place, the producers of the film had succeeded in getting Newman/Haas Racing, a top racing team, to field and maintain an actual Indy car equipped with an IMAX camera; convinced legendary driver Mario Andretti to pilot the camera car; landed Mario and his son, racing star Michael Andretti, as subjects of the film; and secured IMAX coverage of the teams and drivers of the PPG CART World Series on the track and in racing action. To top it all off, the production team had miraculously stumbled across the work of expert car restorer Don Lyons. Lyons was in the process of restoring the wreckage of a classic 1964 roadster — a unique, hand-built machine (the last of its kind ever made) that was driven in 1964 by a rookie driver named Mario Andretti.

Super Speedway was filmed from an Indy car driven by Mario Andretti under real race conditions and at race speeds—the first giant screen film to feature extensive high-speed track action. The Lola camera car was originally driven to victory by Nigel Mansel in the 1994 season.

Once in a Lifetime

Pietro Serapiglia, the producer of Super Speedway, describes acclaimed IMAX® director Stephen Low as “a visionary who makes great films.” Low is also a man who seeks out challenges, and he and his collaborators have pulled off a remarkable coup with the making of Super Speedway. Some of the world’s most respected racing personalities and organizations came together in a unique collaboration with The Stephen Low Company to help in the creation of the film, making it a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for audiences to experience the thrill, magic and danger of Indy car racing.

From start to finish, the Super Speedway project took just over four years. By the time the pieces of the production puzzle fell into place, the producers of the film had succeeded in getting Newman/Haas Racing, a top racing team, to field and maintain an actual Indy car equipped with an IMAX camera; convinced legendary driver Mario Andretti to pilot the camera car; landed Mario and his son, racing star Michael Andretti, as subjects of the film; and secured IMAX coverage of the teams and drivers of the PPG CART World Series on the track and in racing action. To top it all off, the production team had miraculously stumbled across the work of expert car restorer Don Lyons. Lyons was in the process of restoring the wreckage of a classic 1964 roadster — a unique, hand-built machine (the last of its kind ever made) that was driven in 1964 by a rookie driver named Mario Andretti. And finally, actor and team co-owner Paul Newman would agree to lend his seasoned voice to narrate the film, adding a further touch of authenticity and distinctiveness to the project.

For Real

Stephen Low and Mario Andretti were only interested in shooting a film that conveyed the reality of driving a race car at speeds up to 240 miles per hour. On the track, Andretti proved to be an exceptional camera operator with a natural feel for shooting, an instinctive finesse that contributed strongly to the power of the final movie experience. “Stephen explained that even with that big lump of a camera on the car, he expected me to drive as hard as I could,” says Andretti. “And I thought, now you’re talking my language. I didn’t want to just cruise around and be a donkey out there. They were looking for somebody who really wanted to put some teeth into the deal. I said to him, ‘Well, okay, let’s not use any trickery in the filming, no speeding up the camera. Let’s just be realistic. If we can represent reality, then I’ll do it.’ And we never looked back.”

The First Spark

The production of Super Speedway got under way in 1993. Low, a longtime enthusiast of open- wheel racing, had harboured the dream of producing a film about auto racing since his father, acclaimed filmmaker Colin Low, filmed Jimmy Clark winning the Indy 500 in 1965. There was no doubt in Low’s mind that he had chosen the perfect subject for an IMAX film: Indy car racing was the most competitive form of racing, the cars were technologically the most interesting, and the types of race courses—ovals, big ovals, road courses and city courses—were the most varied. Pietro Serapiglia recalls that Low had plans for an Indy car film in mind as they were completing Low’s previous film, Titanica: “I remember we were in Newfoundland finishing the movie about the Titanic when Stephen said, ‘think Indy car’.” Later, Low took Serapiglia to a race, where he felt the adrenaline rush of thousands of fans as the race reached its climax. At that moment he was sold on the idea, and the experience fueled his ambition to raise the financing for the film.

Fueling the Project

The initial step for Low was to convince executive producer Goulam Amarsy that an IMAX film about Indy cars was a worthwhile project. Amarsy quickly recognized that Low’s keen passion for the subject coupled with the potential power of car racing on the giant screen made for a good project. Low and Serapiglia both feel that without Amarsy’s efforts in lining up sponsors and securing financing, as well as obtaining the cooperation of key people in the racing world, Super Speedway could not have been made.

Raising funds for the project was accomplished over a three year period. Serapiglia and Amarsy, persistent in their efforts, were helped by Low’s reputation for successful large-format films, the hot subject matter and the growing market for giant-screen entertainment. Because of Low’s name, they were ultimately able to attract two principal sponsors (Texaco and Kmart), secure financing from the Banque Nationale de Paris, and convince the Quebec film-funding agency, SODEC, to back the agency’s first IMAX project from Quebec.

The company adopted a shrewd strategy by approaching theatres individually in an effort to open up their own international support network — a network of theatres that would commit financially to exhibiting the film before it was even fully shot. The strategy was successful. Initially in 1993, The Stephen Low Company succeeded in securing pre-lease agreements with four IMAX theatres. To attract other venues, Serapiglia showed theatre managers an assembly of test footage that Low had shot in late 1995 and early 1996 at tracks in Sebring and Homestead, Florida. When they saw the material the managers were stunned by the magic of experiencing Indy car racing on the IMAX® screen and rushed to sign pre-lease agreements. Altogether, 37 theatres signed early-lease agreements for the film — far more at that time than any other project in the history of large-format cinema.

Opening the Doors

Making the film meant finding an Indy car team willing to cooperate with the project. This was not an easy job. The world of Indy car racing is a closed one, and not just anyone can enter with camera loaded and ready to shoot. Low needed a team that would allow the production crew to get behind the scenes as the team pursued a championship over the racing season, something that had never been done in other racing movies such as Winning, Grand Prix, and Le Mans.

The only Indy car team to show an interest in the project was the team run by Carl Haas and Paul Newman, which in 1996 was fielding cars driven by Christian Fittipaldi and Michael Andretti.

According to Low, every film has a godfather, and in this case it was Neil Richter, the man in charge of finances for Newman/Haas Racing. Richter was very interested in the film from the beginning, and was able to convince Carl Haas that the project should be taken seriously. He was also instrumental in opening doors at Championship Auto Racing Teams (CART), the governing body for Indy car racing, and getting the attention of other racing teams. Low’s credibility as a filmmaker was an important factor; without it, Richter would not have pursued the concept. “At the end of the day,” he says, “you want a high-profile, quality product. The people who are producing it have got to be top-notch.”

Behind the Wheel

Once the Newman/Haas team was involved, Low had to find out if a 1,600-pound Indy car with a large IMAX camera mounted on the roll-bar could reach race speeds. This was a perilous proposition: Indy cars are delicately balanced machines worth close to half a million dollars, and their performance is altered even by the weight of a few extra litres of fuel. Could the car safely withstand the aerodynamic drag and extra burden of a camera and mount?

The camera car during practice with the IMAX camera mounted in front of the driver. (Professional driver on a closed track. Don’t try this at home!) Photo: Patrick Gariup.

To develop the specialized mount for a real Indy car, the team turned to race engineering expert Alec Greaves. Working with camera specialist Bill Reeve, Greaves engineered a mounting system that allowed the camera to be mounted in a range of postitions on the car: on the nose cone, off the side pods, over the roll bar and directly under a specially modified rear wing. Combined with varied camera angles and lenses, the mounting system provided an infinite number of fixed position mounts on the car including the side-views that were ultimately to capture neck-to-neck duels with drivers Mark Blundell, Bryan Herta and Al Unser Jr.

The insurance companies, racing officials and other drivers were still nervous. This was where racing giant Mario Andretti came in. Originally, Low had thought he would do the filming using Michael Andretti between racing engagements. It soon became clear that the logistics of this were impossible. At the urging of Newman and Haas, Low and his team approached the elder Andretti about testing the car and camera. Andretti, recently retired but eager to get back behind the wheel of a race car, was intrigued by the project and agreed to meet Low.

Andretti was skeptical at first: “I looked at the car and thought – oh man, we’ll be lucky to average 150.” However, all doubts about the ability of a camera-equipped car to run at racing speeds disappeared when Andretti took the car to 210 miles per hour in his first practice session. But the initial tests failed anyway: as the car reached speeds upwards of 200 miles per hour high-frequency vibrations from its engine tore the camera’s electronics apart. The team persevered, and after engineering some additional dampening into the camera mounts, was finally able to resolve the problem. It was only when Low reviewed the first rushes and saw how amazing 200 miles per hour looked in IMAX® that he realized he could make the movie he had long dreamed of making.

Low found that Andretti was the perfect person to operate the camera. Andretti was able to switch the camera on and, in Low’s words, “go crazy for a lap or two or three.” Low came to respect Andretti’s instincts about what to film. His vast experience in auto racing and his thoughtful approach to the Super Speedway project enabled him to recognize a good opportunity when he saw it.

It Must Be Something Good

Andretti’s involvement was critical to the success of the project. As Serapiglia describes it, “The day we got Mario to participate was the day other people became interested in the film. They said, ‘Hey, if Mario is doing it, it must be something good,’ and more doors swung open.” CART agreed to work with Low in May 1996, organizing four races for Andretti to drive in with the camera on the car. Securing the cooperation of the other 26 CART teams was another story; Low, Andretti and company had to overcome the various fears of the teams, the sponsors, the drivers and the insurance companies. In time, thanks to Andretti’s influence, Low’s reputation and Richter’s enthusiasm, the doubts of the other teams subsided, then disappeared completely when they saw the initial footage.

Shooting in the rain. Mario Andretti in the camera car (left), Michael Andretti out front. Photo: Patrick Gariup.

Michael Andretti hot on the tail of the camera car driven by Mario Andretti at Homestead Motor Speedway, Florida. (A frame from Super Speedway.

Enthused by the calibre of the IMAX racing footage, many of the drivers and teams became actively involved in making the project work. Drivers such as Mark Blundell, Bryan Herta and Al Unser Jr., were keen supporters, sacrificing time from tight schedules to race Mario Andretti and the camera car in specially arranged exercises.

The Car

The camera car driven by Mario Andretti was a two year-old Indy car acquired from Newman/Haas and maintained by Newman/Haas mechanics. The same car was driven by Mario Andretti and Nigel Mansel in competition in the 1994 PPG CART World Series.

While the engine output of competing CART cars is constrained by stringent rules, the camera car was not under similar restriction. Competing cars are equipped with a mandatory ‘pop-off’ valve which governs the maximum power engines can generate and helps keep race speeds within acceptable limits. The ‘pop-off’ valve on the camera car was deactivated, providing the machine with significant additional power. The aerodynamic design features of the older car also generated greater downforce than has been available to cars under more recent CART rules. (Downforce, the product of wings and body shape, is the aerodynamic force which helps keep a fast moving car pressed to the track).

The superior power of the camera car helped offset the encumbering effects of camera weight and drag, while superior downforce helped counteract the destabilizing effects which resulted from having the camera mounted high above the chassis. Both power and downforce provided Mario Andretti with the speed and control necessary to manoeuvre with the competing cars and drivers from the PPG CART World Series.

Specially placed microphones on the car accurately picked up the sound of the car and the unique sound experiences of driving in the racing environment, including the powerful oscillating effect created as the car blasted along speedway walls.

Filming On the Track

Initially, shooting was accomplished at team practices only. Mario Andretti and the production team and car crew, worked in narrow windows of opportunity, sometimes with over 20 cars on the race course at once. Coordinating via radio, the production team helped synchronize the efforts of the different teams and drivers, and kept camera car operator Mario Andretti apprised of the constantly changing situation on the track.

Participation in the project reached a climax when the full support of CART and the teams was obtained to put virtually all the cars in the series on the track for the camera just moments prior to the start of actual races. Twenty-five cars and drivers blasted around courses in Toronto; Brooklyn, Michigan; Lexington, Ohio; and Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, just minutes prior to start of each event. This unprecedented exercise provided Mario Andretti and the production crew with a truly unique opportunity to record the racing experience from the driver’s viewpoint.

Mario Andretti with the IMAX camera mounted overhead during preparation for filming at the Toronto Molson Indy. Photo: Patrick Gariup.

Mario Andretti climbs into the camera car to begin filming an on-track sequence. Photo: Patrick Gariup.

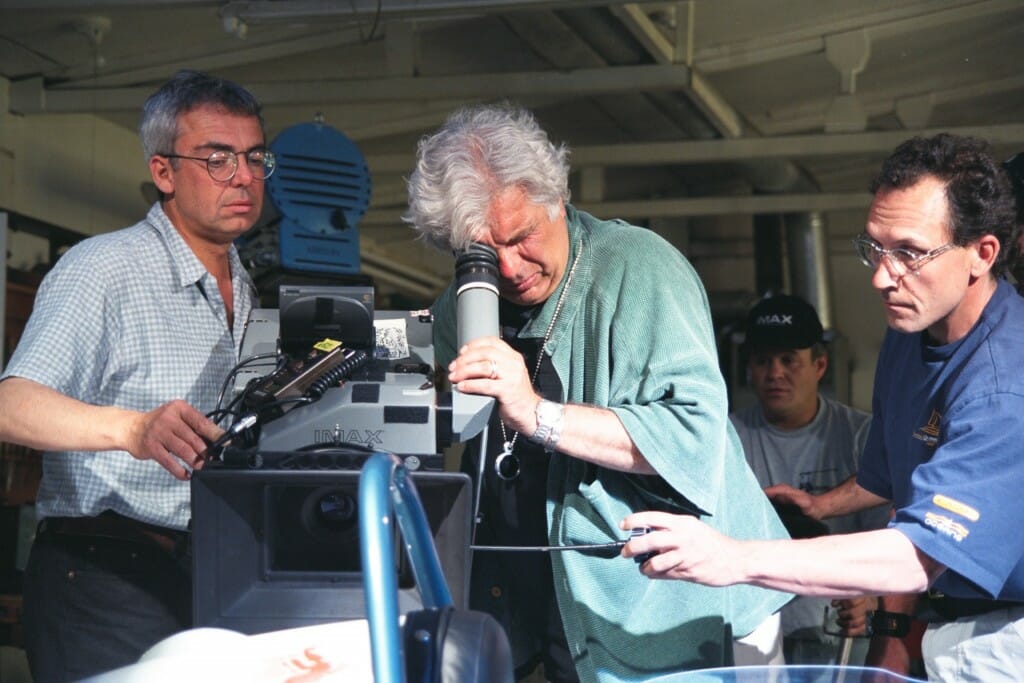

Filmmaker Stephen Low (left) and IMAX camera specialist Bill Reeve (right) working trackside with the IMAX camera and telephoto lens.

Working around the tight schedules of the teams, the Super Speedway crew was ultimately able to cover dozens of practices, including action at Sebring FL and spring practice at Homestead, FL. Altogether they covered five key race events: the U.S. 500 event at Michigan International Speedway, and races in Detroit, Toronto, Mid-Ohio (Lexington, Ohio), and Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin. Through the effort, the production team secured more than enough material to create an extraordinary experiential portrait of the sport.

The Characters

As an IMAX filmmaker, Stephen Low is in a class by himself. He brings drama to the art of documentary filmmaking by finding larger-than-life characters and telling their stories. Indy car racing is an extraordinary event. Low knows that the men who compete in these races have a burning desire to push themselves and their machines to the edge of physical possibility. In this sport he has found his ultimate characters: Mario Andretti, one of the most successful men in auto racing history, and his son, Michael, himself a champion and veteran of the sport.

Low recognized the importance of placing Mario Andretti at the centre of the film. Mario Andretti’s experience spans 30 years of racing technology, as well as countless milestones in the ever-evolving sport of racing and he has been teammates with, and raced against, many of the world’s best drivers, including his own son.

Low had an additional motivation. As Low explains it, “I like eccentric people. The characters have got to be bigger than life, and you go with it. That’s the essence of filmmaking. I was attracted by Mario because he’s a funny guy. He was a great choice for the key character because of his charm and thoughtfulness. Obviously, he’s an incredible driver, and Newman/Haas wanted him to pilot the camera car, but I didn’t have to make a film about him. I could have made it about Michael Andretti or Indy cars in general. But I thought Mario was really interesting. Anybody who has a pig given to him by his wife and who hates it at first but then becomes its best buddy, well, he’s got to be quite a character.”

Mario Andretti pilots an ultralight with the IMAX camera for a shot in Super Speedway. Photo: Patrick Gariup.

Mario Andretti at the controls of an ultralight during filming of Super Speedway. Photo: Patrick Gariup.

The crew of Super Speedway take a break during filming with Mario Andretti and his pet pig. Photo: Patrick Gariup.

While making the movie the two men developed a very special relationship with a tremendous amount of mutual respect. By showing a genuine interest in all aspects of Andretti’s life, Low got Andretti to reveal himself. And so Mario Andretti, originally approached for the crucial role of driving the camera car, soon became a key subject in the film as well.

Building the Story

Super Speedway delves into the death-defying drama of Indy car racing and delivers several interwoven story lines. At the core of the film’s action is Michael Andretti, taking on the challenge of testing a newly fabricated car and, ultimately driving it in hot pursuit of the championship in the PPG CART World Series. Michael’s struggle is seen in part through the eyes of his father, Mario, who participates in testing the new car and reflects on his own racing experiences and on the art, science and risk of high-speed competition. As a driving legend and as Michael Andretti’s father, Mario provides audiences with insight into the driver’s psyche, the balancing of risk and opportunity, and the unique relationship that exists between two generations of champions.

Set against the drama of the track are two story threads that follow the extraordinary craft of creating Indy cars: the building of Michael Andretti’s state-of-the-art Indy car at the Lola plant in England and the restoration of a car from an earlier generation, a 1964 roadster — a thoroughbred once driven at Indianapolis by Mario Andretti.

Early in the project the production team traveled to chassis manufacturer Lola Cars and engine manufacturer Ford-Cosworth in England to film the creation of a new racing machine for the Newman/Haas team — Michael Andretti’s car for the approaching season. On the giant screen in time-lapse, viewers witness the shaping of the powerful new beast, including its magical assembly by engineers at the Lola plant.

Filming at Lola in the UK. Filmmaker Stephen Low discusses the setup of a shot with Lola personnel and film crew. Photo: Patrick Gariup.

A body mold for an Indy car is shaped by a computer-driven milling machine. The IMAX camera dolly is at right. Photo: Patrick Gariup

Will the newly finished car perform? Will it be fast and will it be forgiving? To win races and to stay alive, the driver must be able to feel the car’s performance limits and consistently take the machine to this edge without straying beyond. As Michael Andretti and Mario Andretti blast around the track testing the untried machine, the audience experiences the tension and viscerally understands the risk.

Director of photography Bill Reeve works with the IMAX camera inside the chassis of the roadster during filming of a restoration sequence for Super Speedway.

An important story counterpoint for Super Speedway presented itself when Low learned of auto restorer Don Lyons and his plans to rebuild the 1964 Dean Van Lines Special roadster. Mario Andretti had driven the car as a rookie, and when Lyons discovered it in a chicken coop in Indiana, Low knew he had found another dramatic hook for his film. Lyons has restored more than 50 vintage automobiles since he began his hobby at age 14, and in the film, his passion for his craft is readily apparent as he rebuilds the wreckage of the roadster, striving to restore it to its original glory.

Filming the roadster restoration process. Director Stephen Low (left) and DOP Andy Kitzanuk (center). Photo: Patrick Gariup.

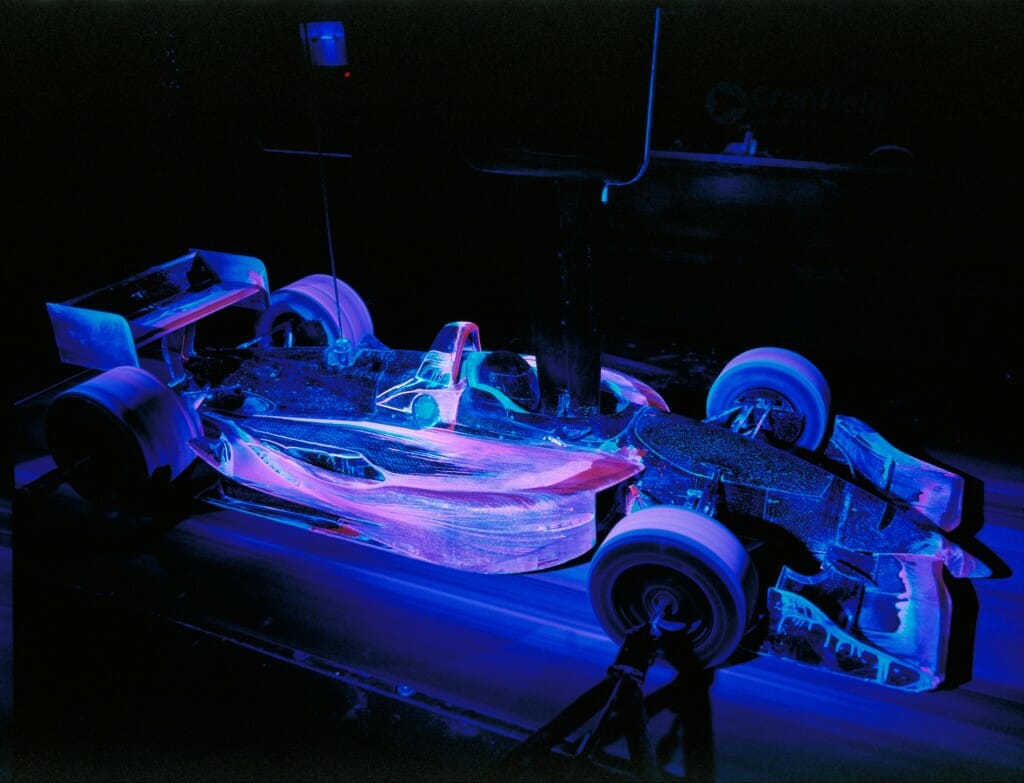

The art and technology of building fast cars has undergone a radical transformation since the 1960s, when tubular, steel-framed roadsters like the 1964 Dean Van Lines Special dominated the Indy car circuit. In the old days, car manufacturers attempted to build faster cars by increasing engine horsepower. Today however, all aspects of a car’s design including engine power, are governed by the rules of the sport. These rules change regularly in an effort to limit speeds and enhance safety. In this environment, teams work within and around the rules to achieve the competitive edge; aerodynamics play a key role in the process, making wind-tunnel testing an essential step in the shaping of winning cars. In the film, the Newman/Haas team turns to wind-tunnel testing, using a model in an attempt to fine-tune the aerodynamic forces at work on Michael Andretti’s finished car—ultimately they must make the car more controllable and more predictable.

Technicians prepare an Indy car model for testing in a wind tunnel at Cranfield University Centre for Aeronautics in the UK during filming for Super Speedway. Photo: Patrick Gariup.

The wind tunnel test from Super Speedway. Fluorescent dyes track the turbulent air flow across the car’s surfaces.

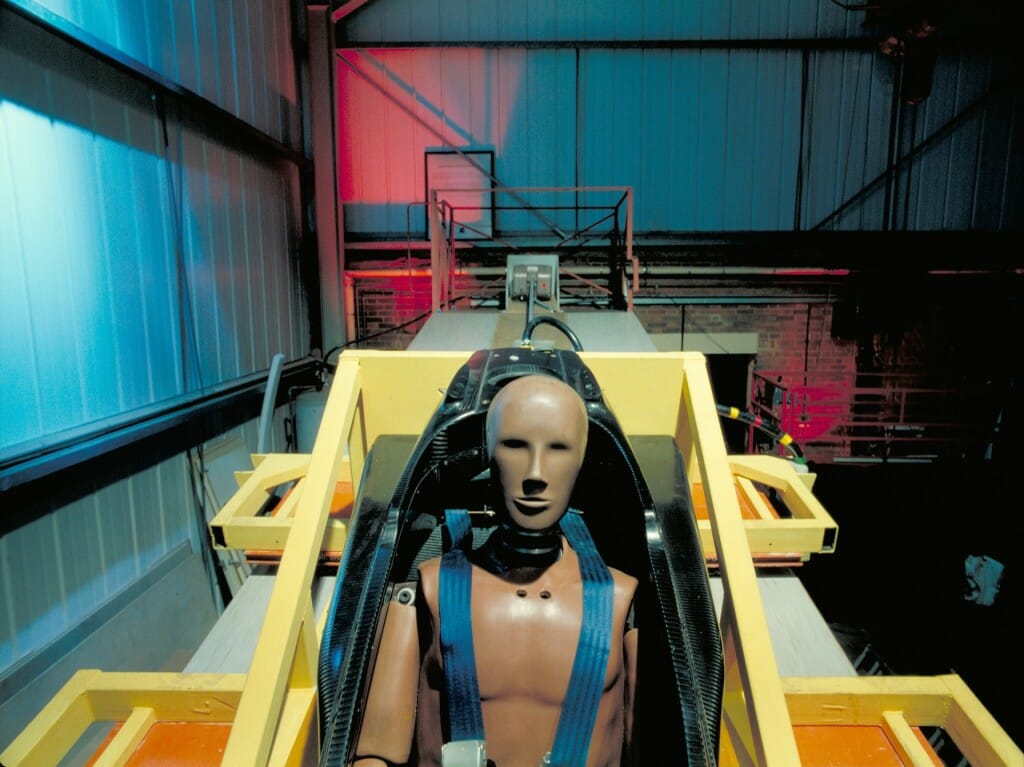

A crash test dummy prepares for the worst during crash testing of an Indy car nose cone. (From Super Speedway.)

In Super Speedway, classic archival footage depicts some of racing history’s most dramatic crashes, calamities that are, for drivers, an everyday risk. Although the sport has become progressively safer, it can still yield instantaneous tragedies, a fact driven home for the production team when rookie driver Jeff Krosnoff and a track marshall were killed during a race event being covered for the film.

Super Speedway culminates in a dramatic portrayal of the racing season. Track action was shot with an on-board IMAX® camera and a full field of competing CART teams during specially scheduled pre-race exercises, as well as track-side during actual race events. In the film, never-before-possible giant-screen footage captures the drivers, machines and teams of the PPG CART World Series battling each other for supremacy; among them are Michael Andretti and the Newman/Haas team. From the pits, a proud, encouraging and sometimes apprehensive Mario Andretti looks on.

The season is a challenging one, and in the end it is driver Jimmy Vasser that takes the championship on points, but Michael Andretti and the Newman/Haas team triumph as well. On-screen Michael and other drivers in the winner’s circle douse the media and audience with jets of champagne. Michael wins five races — more than any other driver in the series.

Mario Andretti at the wheel of a restored roadster he first drove as a rooky at the Indianapolis 500. Photo: Patrick Gariup.

Don Lyons’ patient restoration work on the 1964 Dean Van Lines Special is finally completed and the sparkling white and chrome roadster is triumphantly rolled out of the workshop. In Super Speedway’s concluding moments, Mario Andretti is reunited with the car that once initiated him, as a young man, into the high-profile world of Indy car racing. In a final stroke of luck, the production team managed to locate three decade-old archival black and white footage of a young Mario Andretti, strapping himself into the same roadster for an historic career-launching run.

In the present, Mario Andretti, veteran of thirty-six years of high-speed competition, straps himself once again into the great old roadster and roars off through the fall colours of the Michigan countryside.

Super Speedway – An IMAX® Experience™

The IMAX experience of Indy car racing bears no relationship to the television experience. On-board action as seen through the narrow window of television has the effect of slowing down the action, and as a result television does not give a true picture of what the racers see and feel. Mario Andretti should know. According to him, “This IMAX stuff will keep you on the edge of your seat because everything is happening the way we see it.”

The way producer Pietro Serapiglia sees it, “Super Speedway is like no other racing film ever made. In IMAX, 200 miles per hour is suddenly wonderfully fast. Nobody in the history of cinema has ever experienced what it’s like to sit on a roll-bar. In the film, all that’s missing is the wind. For the first time audiences will viscerally know what auto racers experience—the speed and the danger.” Stephen Low says, “For the better part of the century people have wondered what it was like to sit in the cockpit, and now we’re going to show them.”

Links

More about the film: Super Speedway page.